Scientists since the ancient Greeks believed that a substance called aether, also spelled ether or called luminiferous ether, filled space and allowed the transmission of gravity, light, and even animating spirit. It was weightless and transparent, and therefore stubbornly undetectable, but it was everywhere.

Like air, everything moved through it, and everyone shared it.

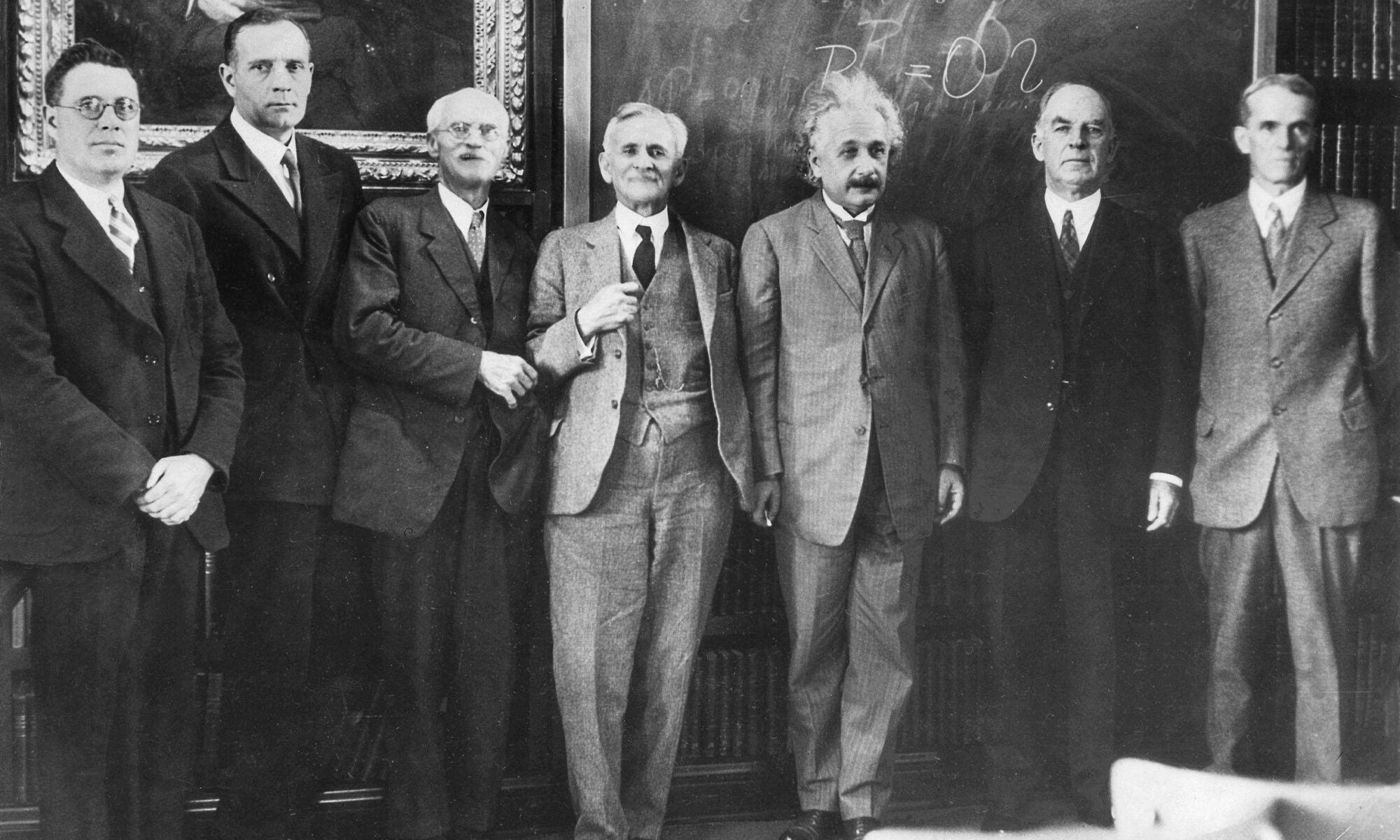

As the structure of matter and the nature of light became better understood in the 19th century, experiments were devised to put that belief to test. A scientist named Albert Michelson led that charge, having proposed experiments to measure the speed of light while still in the US Navy in 1869 (he’d go on to win the Nobel Prize in 1907 for his pioneering work in spectroscopy).

In the late 1800’s, Michelson decided to use his understanding of the speed of light to test for the presence of aether by literally looking for the “drift” that the Earth should create by moving through it.

His failure to find it — the experiments yielded a “null result” that didn’t mean they’d failed but rather that his data didn’t conform to his expected measurements — led Hendrik Lorenz to develop his famous contraction equations. Later, Albert Einstein credited the experiments as confirmation of the assumptions underlying his special theory of relativity.

Then, about a century after the Michelson-Morley experiments, astronomer Vera Rubin found proof that the cosmos is filled with something she called “dark matter,” and which affects the movement and interaction of everything we see. There are other, more complex theories about spacetime that involve multiple dimensions and even the idea that tangible reality is a fluid and unknowable charade.

We move though the cosmos and it moves through us. We are connected after all.